Is it Enough to Imagine Sisyphus Happy?

And one day, you are foolish enough to retrace your steps, thinking that the exceptional can be exceptional again: Time travel and magical realism in Carpentier's The Lost Steps

The Lost Steps was written by renowned Cuban Novelist, Alejo Carpentier in 1953. It is his most famous novel and has been translated into twenty different languages. Alejo Carpentier (1904 - 1980), was born in Lausanne, Switzerland but grew up in Havana and identified as Cuban throughout his life. He had strong political opinions and often aligned with leftist political ideologies. Carpentier supported Fidel Castro’s Communist Revolution in the mid 20th century and was both jailed and exiled for his beliefs.

Every time I read an authors’ biography or get an inkling of their beliefs I am always reminded about how our creative work is influenced not only by the lives we lead, but also our environment. There’s something about that feels very homey to me, to acknowledge that our creativity is an extension, an ode, or a reconciliation of what happens within our lifetime. To know that we can never really be without bias, and that our works of art are simultaneously reflective and emblematic of our circumstances. Positioning an author is an important reminder to readers to analyze texts with a more curated and holistic lens.

The Lost Steps

The Lost Steps or Los Pasos Perdidos explores the life of an unnamed intellectual, a musical composer, and dissatisfied man living his Sisyphean-like existence in marketing and advertising and finding little to no meaning in the corporate world:

“Now I am back outside looking for a bar, if I walk too long to find a glass of liquor, that long familiar depression will invade me, making me feel like a prisoner with no exit in sight, despairing at my inability to change one single thing about my existence, overruled by the will of others who barely leave me the freedom to choose which meat or grain I will have for breakfast each morning.” (p. 11)

He is offered the opportunity to travel to South America to locate prehistoric musical instruments and their ancestral function. Initially, he doesn’t think much of this opportunity, instead viewing it as a way to escape his depressing life and have a little vacation with his lover. However, as he journeys he finds himself amidst a change not only in landscape, but also in perspective, as he embarks on this cultural, geographical, and sentimental journey, he finds himself at the very origins of humanity.

Carpentier uses magical realism or as he called it, “lo real maravilloso”, which is a literary genre that blends the supernatural with the ordinary. Magical realism doesn’t quite dip into fantasy or the supernatural, but rather, it’s more about finding magic in things that would otherwise be considered ordinary. It adds an element of whimsy into a story without taking away from reality. The Lost Steps explores the idea of time travel through the notions that we can be uncertain about time and that we can experience time again. In his travels, our protagonist reflects:

“It is, perhaps, the year 1540. But no. The years decrease, dilute, desist in the vertiginous process of time. We have not yet entered the sixteenth century. We are living long before. We are in the middle ages.” (p.141-142)

Throughout the novel our protagonist travels chronologically through time. As he first enters the Latin American capital —he thinks of revolution and architecture, marvelling at the sights, then he travels to a provincial city where he notices a more nineteenth-century atmosphere reminiscent of Romanticism, he continues his journey to the village of Santiago de los Aguinaldos, which represents the colonial period of rubber tappers and miners, and finally, he enters an uncharted forest glimpsing a time that preceded any human life.

You know that feeling when you visit your hometown, maybe some things have changed, but much of it remains the same? You go to the mall and there are cars on display in the foyer, there’s an old but familiar smell, the floors are cracked, and the stores are spotting neon signage reminiscent of the 90s. Or maybe you’re visiting a grandparents house and they have plastic covers on the furniture and a layer of dust so old it brings back allergies long forgotten. It smells like mothballs and jasmine, and jeopardy plays softly in the background. An effective form of time travel where the setting, irrespective of ‘time’, is representative enough to make you feel as though you have actually time travelled.

Our protagonist is a man who yearns for a time past, his current dissatisfaction with life only exacerbates the yearning:

“With these familiar images before me, I asked myself if men in ages past had also longed for ages past, as I yearned on this summer morning—as if I myself had known them—for ways of life man had lost for all time.” (p.27)

In his quest to find ancient musical instruments he is introduced to the Pathfinder, a man who knows the jungle and describes it as, “a vast expanse of mountains, abysses, treasures, wandering peoples, vestiges of disappeared civilizations; it was a world unto itself, with food for its fauna…it was a hidden nation, mapped in code, a vegetal country with few ways in.” (p. 101)

And it is here, in the hidden city of the Pathfinder, Santa Mónica de los Venados, that our protagonist stumbles upon what he believes to be an Arcadia, or a utopian idyllic, an unspoiled countryside; wherein the only social order that exists is the one that is imperative to ensure survival, just as at civilization’s origins.

“All around me were people devoted to their vocations in the tranquil concert of the errands of a life subject to primordial rhythms. I had always seen the Indians through fantastical stories, as beings on the margins of man’s true existence, but in their medium, their environment, they were absolute masters of their culture. Nothing was more alien to their reality than the absurd concept of the savage. The fact that they were unaware of things that for me were essential and necessary in no way relegated them to the primitive…Here there were no useless occupations, as mine had been for so many years.” (p. 138-139)

The protagonist makes the decision to stay in Santa Mónica de los Venados, committed to his realization that there were still large parts of the world whose inhabitants were oblivious to the chaos of the present day.

“They still possessed a certain animism, an awareness of ancient traditions, a living memory of myth that attested to a culture likely more honest and valid than the one we left back there.” (p. 99).

Not only does disdain grow for ‘back there’, but the protagonist starts to believe that here in this village life would be better in every conceivable way. He is fascinated by the rituals of the people, and in particular their death rituals. The composer in him begins to stir, feeling a sudden compulsion to compose a threnody, or a song used as a way to both remember and honour the dead. He begins to compare Western traditions and understanding of death with his observations in this small village:

“The men in the cities I’d lived in no longer knew the meaning of these voices and had forgotten the language of those who know how to speak to the dead…I remembered then just how despicable and mediocre death had become to the men of my Shore—my people—with their cold funeral homes…rented furnishings, and hands stretched over the corpse in expectation of recompense.” (p. 105)

Like any artist, he spends weeks fervently devoted to his craft, filling his journals and running through them like candy. He soon realizes that he needs the tools of life “back there”, to help him finish composing his threnody. But more than that, he starts to desire recognition for his work, the pull to share his composition among his musical and intellectual counterparts. No sooner does he have these thoughts, does a plane land, specifically looking for him, his family thinking him lost for weeks.

At this moment, he realizes that this city, his hidden oasis, lies just three hours from the capital. He thinks about the difference between here and back there, what feels like four centuries and the very origin of life, is traversable by 180 minutes. This thought both distresses and comforts him, he is determined to come back to Santa Mónica de los Venados, and that gives him some breathing room to leave and appease the people at home, share his threnody, and settle his affairs.

As you can imagine from the title of the novel, coming back is a lot more difficult than our unnamed protagonist had initially thought. It is here our protagonist remarks on perhaps the most famous of quotes from the novel and certainly the most transferable:

“You dwell in ignorance as you embark upon new roads, and do not recognize marvels as you live them: stepping out past the familiar, beyond what man has cordoned off, you grow vain in the privilege of discovery, and think yourself the owner of unknown paths, and you tell yourself you can repeat this feat whenever you wish. And one day, you are foolish enough to retrace your steps, thinking that the exceptional can be exceptional again, but when you return, you find the landscape changed, the reference points erased, the informants’ faces different.” (p. 218-219)

Character Analysis

I want to take a moment to acknowledge our unnamed protagonist as an unlikeable character. He is at best uninformed and at worst problematic. Despite his efforts, our protagonist missed the mark many times on the path to “finding himself”. Much of his scruples with the world were self-centred, he doesn’t think much about his impact—especially in a new city with a different culture and set of traditions. He often referenced conquistadors in his journey to explore and toed the line between genuine exploration and a desire to colonize. He was both careless and callous with each of the women that he had relationships with.

Though perhaps, most importantly, none of his travels were informed, thought through, or deliberate, he made decisions on impulse based off of the feeling that life in Santa Mónica de los Venados was better than life back home. I think Carpentier was purposeful in creating this kind of archetype. Not only did our unnamed protagonist not get back to the city, he had a realization about himself. Towards the end of the novel, he says:

“The truth, the agonizing truth—I understand now—is that the people of these climes never once believed in me. I was provisional and nothing more…seen me as a Visitor, incapable of remaining in the Valley of Stopped Time….But none of this is destined for me because the only race that may not flee the clutches of chronology is the race of artists, who must hurry past the tangible testimonies of the day before and anticipate the songs and forms of those still to come… Today the vacation of Sisyphus ended.” (p.223-224)

There is a bend towards the end of the novel that hints at a little more self-awareness for our unnamed protagonist. I appreciate that arc because I think it portrays a realistic depiction of someone’s awareness expanding in a way that allows them to learn from their experiences. I also think it’s Carpentier’s way of reminding us to think about our impact on the earth and on each other, how we live interconnected lives that affect one another. In an increasingly individualistic society, it’s easy to forget about that individual impact.

Themes

Time

I really enjoyed this story. In particular, I really enjoyed taking my time with it. In my first read and then later, in my analysis, I felt that there was always something new I’d found to turn over in my mind. I keep coming back to Carpentier’s use of time, time is our one constant and yet it is its nature is to be ephemeral. Is it possible to live through time again? I think Carpentier’s novel proves that you can; and that déjà vu and nostalgia are legitimate forms of time travel.

At the start of the novel our unnamed protagonist is so full of yearning. His experiences of awe and wonder from his travels and in particular the feeling of having gone back in time are poignant, pertinent, and I think, very relatable. Who doesn’t think about travelling back in time? Similarly, I think it is human nature to feel a certain kinship for the past. Not only do we remember the past more fondly than it occurred, but also we experience what is known as the golden age fallacy, which is a cognitive bias around believing the past is better than the present or future, drawing on selective memory, idealization, and a lack of critical analysis.

How Carpentier uses time is not only clever, but also an important reminder: that in our attempt to study the past or understand our history, we must also make an effort to position ourselves and our relevant privileges. Carpentier tied these pieces together flawlessly for our unnamed protagonist when he starts to gain more self-awareness. At the end of the novel, when he states: “none of this is destined for me, and that [artists] must hurry past the tangible testimonies of the day before and anticipate the songs and forms of those still to come.” He is both alluding to and acknowledging the role he plays now and the importance of living in and for the present day. It reminds me of what George Orwell said in his essay, Why I write:

“In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer.”

Sisyphean Existence + Free Will

I may have unlocked a new favourite genre while reading The Lost Steps and its more existential themes. There were a lot of references made to Sisyphus which I think is even more relevant today than it was seventy years ago when the book was first written. If we are doomed to keep pushing the rock up the hill only to watch it fall back down, how can we shield ourselves from despair? I think now of what French Philosopher Albert Camus says in his essay, The Myth of Sisyphus: One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

But is it enough to imagine Sisyphus happy? I think it’s a really good start. I also know there are many societal and systemic factors that impact our capacity to do so. Life is often repetitive and monotonous, it is very normal for it to feel cyclical at times. It takes conscientious effort for us to remain present. As our narrator alludes to at the end of the novel, the vacation of Sisyphus is over, he must go back to pushing the rock that defines him. Though a heady realization, I think it’s freeing too. Is it the rock that defines him or is he defining the rock? Or is it a bit of both? At the threshold of destiny and freewill, how do we make that conscientious effort to find life's joys?

It reminds me of that trending meme on the internet, the one where folks suddenly remember they have free will. While it doesn’t always feel that way when we are encapsulated in the systems that remain outside the realm of our control, it can be helpful to remember the moments we do have control over. What does living in the present moment allow us to experience? I saw a comment on a TikTok video that was really cute but also really kind, the video was of someone feeling excited about trying a new restaurant and the comment was:

“I am really inspired by the way you use your free will”.

The Power of Whimsy

I keep coming back to this idea of finding the extraordinary in the ordinary. Carpentier’s use of magical realism got me thinking about all the ways we can look for elements of whimsy in our otherwise ordinary lives.

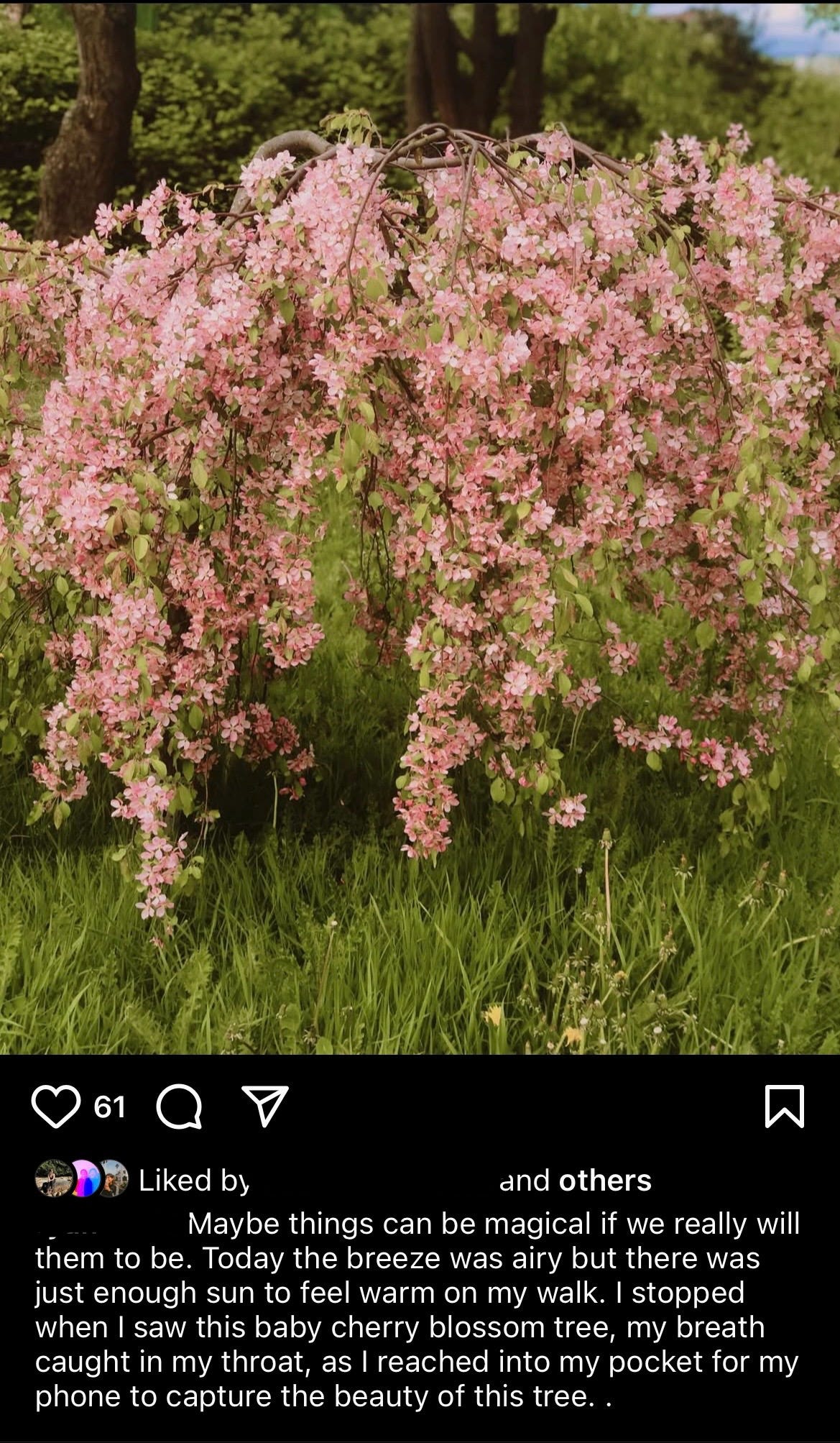

There’s this beautiful tiny tree in a park by my parents’ place. It’s an industrial-ish park by railroad track that they’ve worked hard to keep beautiful. About five years ago, during peak cherry blossom season, I saw this tree with what felt like a new set of eyes, you can read my caption the day I saw it:

I think we all have moments like this. Something strikes us as particularly beautiful or moving or meaningful. Finding the whimsy and the joy in our everyday life takes concerted effort and it’s not always easy, especially when we start to consider the current climate of the world. I would be remiss if in my writing if I didn’t talk about all the ways different marginalized communities may be feeling increasingly targeted in today's time. How we also may be susceptible to yearning for times past like our protagonist (even if we are remembering the past more fondly than it occurred).

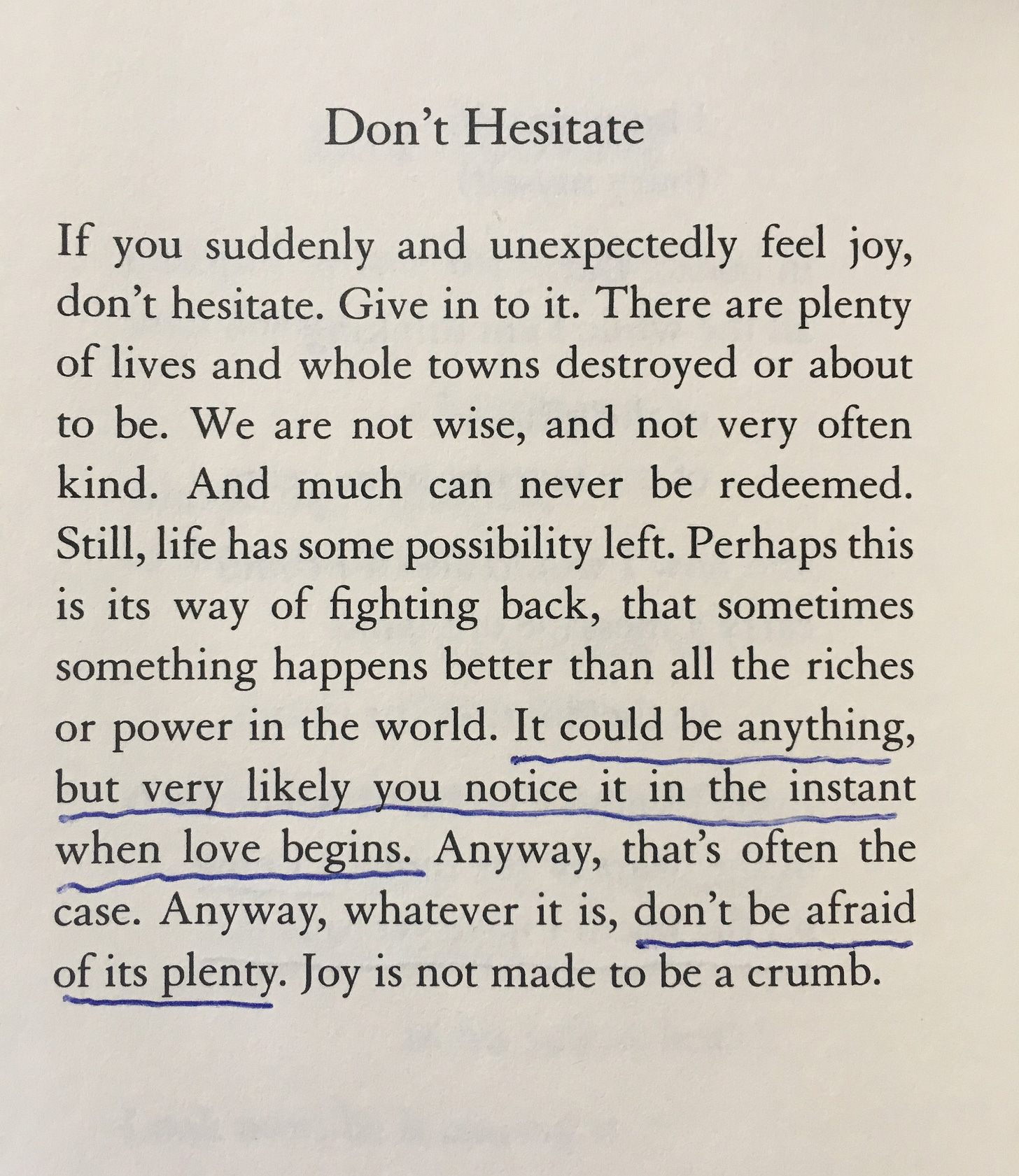

Sometimes when we are overwhelmed with the sheer load of information combined with the constant bombardment of news, it’s hard to figure out what deserves our attention. In the midst of this struggle, I am often thinking about what Toi Derricote says, that “joy is an act of resistance”. If we use our freewill in ways that allow us to engage in joy we are resisting the very plight put upon us, we are effectively saying no, not for me, I choose to remain connected to the joy.

And of course, Mary Oliver knew best:

What gifts are you keeping from the world by staying disconnected from your joy?

—Maryam | مريم | she/her/hers

Wow, this is a breathtaking analysis! As I read your words, I find myself seeing more clearly how, at the crossroads of fate and free will, the weight of the rock and the call of joy are not opposing forces but companions on our journey. Joy, as you illuminate, is something we cultivate—like tending a garden, where the true essence of joy lies not in what we receive, but in how we choose to receive it. Thank you for these beautiful insights ✨️🙏🏽

This is a very well-written article! And is the publication named after something Jungian?